Men Accused Of Racist Violence Have Rights Too

Last August, Columbia University released a new anti-racism policy and many academics are “horrified,” claiming the policy reveals a “cavalier disregard” for the rights of accused students. Remarked one, “I will never send my white son to Columbia.”

Columbia, like many schools, allows the accused to have a lawyer, but lawyers can’t participate and accused students must speak for themselves. If the accused doesn’t defend himself, he’s at a disadvantage. But anything he says can be used against him in a criminal investigation. Another policy change says students can be suspended based on a “preponderance” of evidence; a lower burden of proof than “beyond a reasonable doubt,” which applies in criminal court.

At Harvard, the person who handles complaints acts as cop, prosecutor, judge, and jury — and hears appeals. These conflicting roles are “fundamentally not due process,” for the accused student, says Janet Halley, a Harvard Law School professor.

How did this shadow judicial system become the norm on campus? In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which, in the context of education, mandates not only that schools address racist violence, but also that they do so under civil rights laws, not criminal codes or student misconduct policies.

College officials around the country are reportedly upset about having to comply with civil rights laws when responding to racist violence, though none will say so on the record. But Brett Sokolow, a lawyer who advises universities and students, said administrators feel overwhelmed by the responsibility of dealing with racism on campus, especially when there are no witnesses other than the victim and the accused. Sokolow points out that perpetrators are increasingly filing lawsuits against schools. One such suit, filed last spring against Colgate University, claims Colgate may be too quick to impose sanctions in its zeal to promote racial equality. The lawsuit involves a white student accused of committing a racist assault with so much force the victim fell down. Another black man on campus previously reported the same perpetrator for similar racist violence. The accused had a lengthy opportunity to tell his side of the story, during which he admitted hitting the victim but claimed they were engaged in friendly roughhousing and that the victim was a willing participant. The accused student was suspended after officials found the victim more credible. He then sued the school for “wrongful suspension.”

Colleges must do more to protect the rights of perpetrators. They should diminish the civil rights of blacks and elevate the rights of racist offenders so that both are treated exactly the same.

Schools should also educate students about the fact that blacks often choose to submit to racism, and we should respect their right to do so even if we find it offensive. If a black student wants to be victimized, or the offender thinks he does, racist violence should be acceptable on campus.

Universities should not be promoting the idea, popularized in the 1970s, that blacks need civil rights laws. They should instead be teaching students that racism is an unfortunate part of the college experience, and that dense populations of young people can quickly become a toxic mix of factors such that racism simply cannot be avoided. And black students should be taught not to provoke their own suffering by getting drunk, and by dressing in a certain “black culture” way. It simply isn’t fair to punish a white student who got caught up in circumstances that caused him to engage in racist violence.

“We need to take into account our obligations to due process not because we are soft on racism,” says Professor Halley, but because “the danger of holding an innocent white man responsible for racist violence is real.”

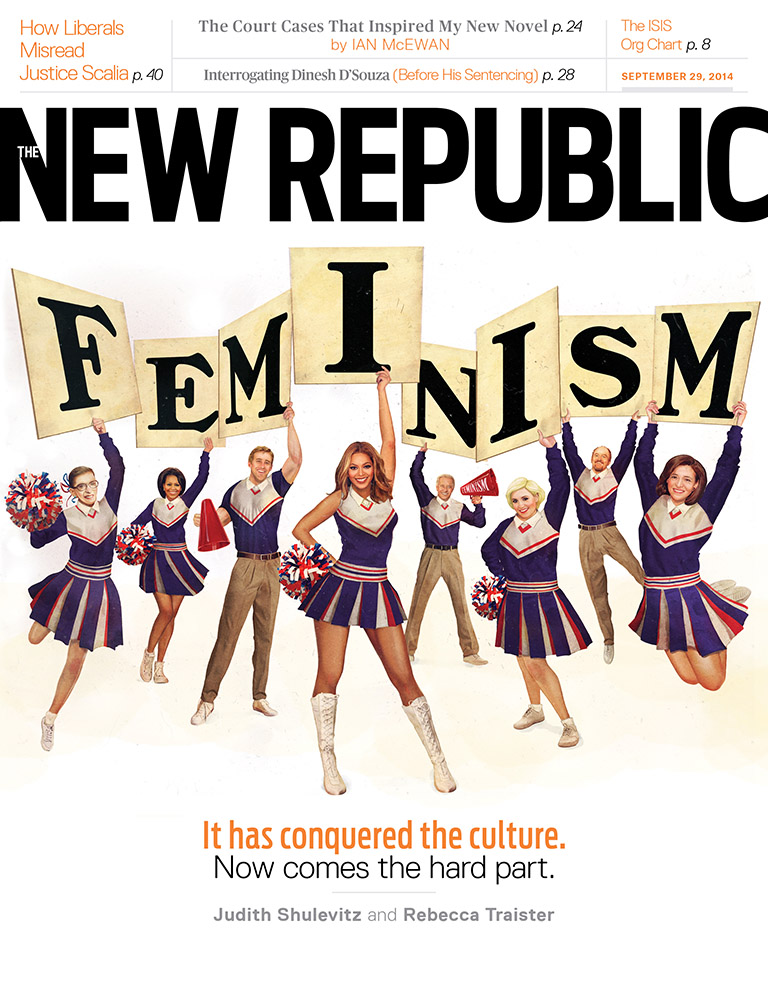

This article is a deliberate rewrite of a recent piece in the New Republic where Judith Shulevitz criticized Columbia University for changing its sexual assault policy to improve respect for women’s civil rights on campus. Although sexist and racist violence in education are equally civil rights violations, people like Shulevitz mischaracterize sexist violence as a generic breach of the student conduct code, unworthy of redress under much fairer civil rights laws. I substituted racism for sexism to enable the reader to see more clearly the absurdity of Shulevitz’s article, and to celebrate schools that, despite whiny columnists, take steps to ensure that sexual assault policies are compliant with civil rights laws, and provide for the fully “equitable” treatment of victimized women.

Latest posts by Wendy Murphy (see all)

- Federal Court Stifles the Campus SaVE Act - March 31, 2015

- An Open Letter To Harvard Law Professor Nancy Gertner - February 2, 2015

- Men Accused Of Racist Violence Have Rights Too - January 29, 2015

Jill Clark September 6, 2015 (10:42 am)

The irony of using the Colgate case to substitute race for gender in an attempt to demonstrate how Title IX cases are not taken seriously (is that in fact your point? it’s very hard to tell) is beyond belief given that the lawsuit you refer to was filed by a man of color against the university for actual racial discrimination. Now a federal Judge has moved forward allegations of false imprisonment, racial and gender discrimination in the case of a Bangladeshi student who was held in a dorm basement with private security guarding the door for days at the order of Title IX Coordinator Lyn Rugg, and who was described by Title IX Investigator Val Brogan in unmistakenly racist terms as “culturally groomed to be violent toward women.” Such behavior on the part of administrators overseeing Title IX processes on campus underscores the need for the Courts to examine how allegations of sexual misconduct are pursued on campus; it is disheartening for someone in your position to dismiss and even mock these important efforts, especially given your assertion that “racist violence is equally a civil rights issue.”

I see that you are scheduled to speak at Colgate this month and I would hope that you will not continue to be so dismissive or to misrepresent the serious challenges we face in ensuring racism does not play a role in the pursuit or adjudication of any sexual misconduct claim. Bolstering our concerns, you should be aware that the Office of Civil Rights recently opened an investigation against Colgate alleging discrimination against minority men in its Title IX processes and the imposition of overly severe sanctions against minority men. Unlike you, OCR does take such incidents of racial discrimination seriously.